From Japan’s Keiretsu networks to modern securitization, credit markets have struggled to balance trust and scale. Shared digital infrastructure offers rails to embed both, unlocking resilient and inclusive capital flows.

Picture Japan in the 1950s. Bombed out factories were being rebuilt, trade routes reopened, and a war-torn nation was searching for engines of recovery. At the center of this revival were networks called ‘Keiretsu’. An interlocking group of banks and companies tied together through cross-shareholding, supply chains and shared governance.

More than just business alliances, they were economic ecosystems built on trust. Inside these networks resources were pooled, risks were absorbed collectively and perhaps most importantly credit was allocated and recycled across the group. A main bank stood at the center, providing steady financing based on intimate familiarity with its firms. Capital moved fluidly across industries, keeping the system stable and fueling long term growth.

The impact was profound. This circulation of credit turned a devastated country into an industrial power, producing global champions like Mitsubishi. Yet their very strength revealed a limitation. Keiretsu thrived on depth not breadth.Trust was intense but confined, circulating within closed circles where information rarely moved beyond the group. This insularity made them powerful engines of national prosperity but incapable of scaling outward. As finance globalized, a system built on exclusivity could never serve as a universal model for credit and growth.

Securitization as the Pathway to Scale

If the Keiretsu showed how credit could flow inside a closed circle, modern day securitization showed how financial engineering could move credit across entire financial systems. The innovation took root in the US during the 1970s, when banks faced a simple but pressing constraint. They were holding vast portfolios of mortgages, auto loans and consumer receivables that generated steady income but tied up precious capital. By pooling these loans and issuing securities backed by their cash flows, lenders could sell exposures into the market, recycle their balance sheets and originate even more credit.

What began as a funding tool grew into an architecture that connected local lending with global savings. The scaling effect was extraordinary. Today, the total outstanding volume of the global securitization market is valued at roughly $15 trillion, a sizable share of the $145 trillion global fixed income market.

Once centered in the US, the market has diversified. Europe remains sizable but fragmented in the years since the global financial crisis. The most dynamic growth is now in Asia, with China emerging as the world’s second largest market. Newer players are also shaping the landscape, Brazil is developing vibrant niches in real estate and agribusiness, while priority sector lending remains a stronger driver in India. What began as an American innovation is diversifying into a more global architecture for capital flows.

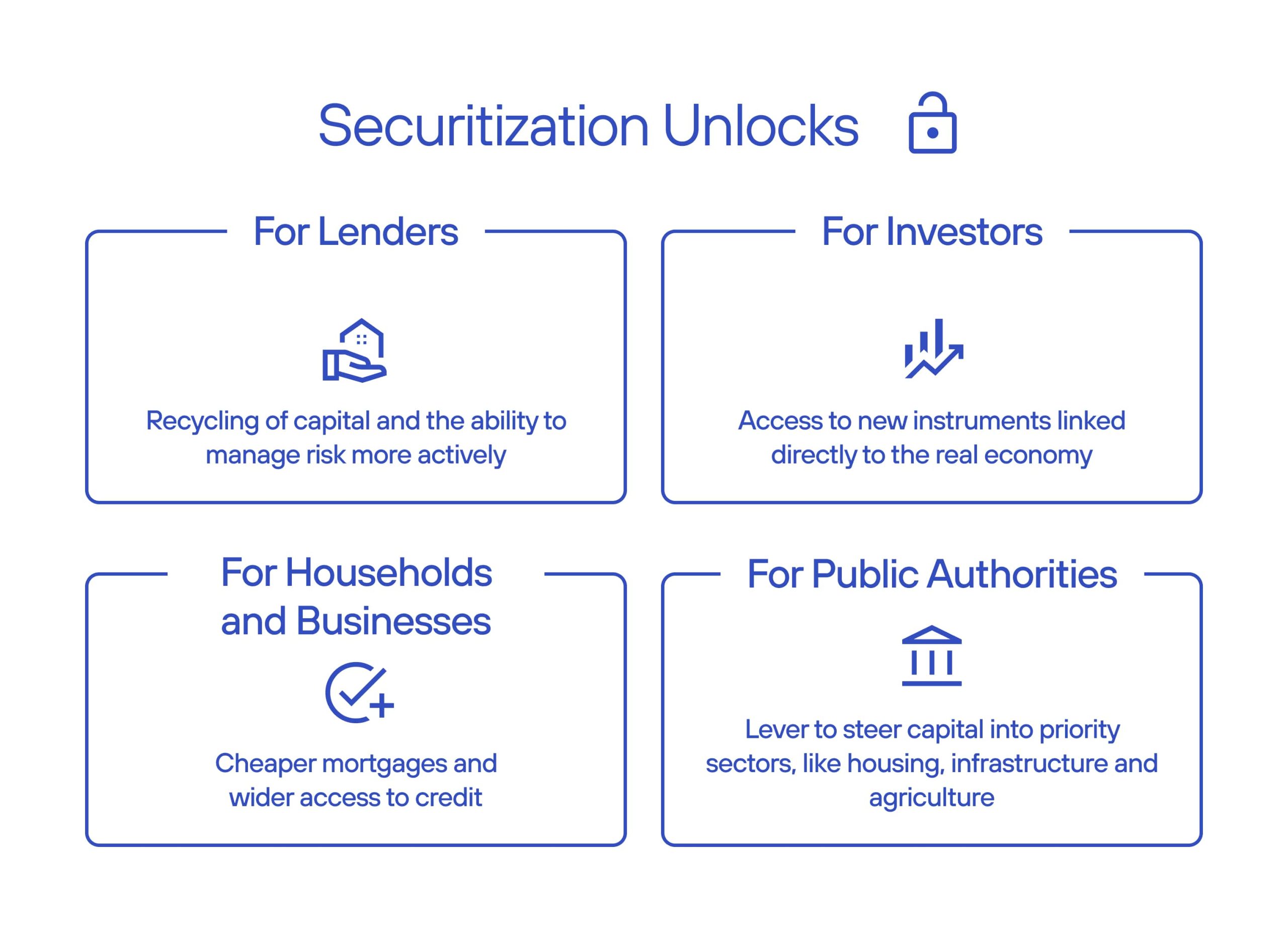

What Securitization Unlocked for Credit Markets

But securitization was never just about moving assets off bank balance sheets. Its deeper impact lies in what it unlocks across the system.

Securitization transformed the structure of credit markets itself. It increased the velocity of credit, multiplying the impact of existing pools of savings. It widened participation by channeling institutional capital into microfinance and SME lending, long constrained by unfavorable terms. It distributed risk more broadly, shifting exposures away from single lenders toward networks of pension funds, asset managers and insurers. And it connected long-term savings to present-day needs, enabling workers saving for retirement in one country to finance homes or schools in another.

But the same mechanics that gave securitization its reach also made it fragile. Complexity multiplied as loans were sliced into tranches and sold to investors with little knowledge of the underlying borrowers. Trust was outsourced to rating agencies, intermediaries and static reports that offered no real-time visibility. Incentives misaligned as originators passed on risk, weakening the discipline of underwriting. The 2008 global financial crisis exposed these flaws brutally as subprime mortgage securities collapsed and cascaded through the system. Reforms in the aftermath restored some confidence but left the market burdened with heavier compliance, slower issuance and higher costs.

If Keiretsu embodied depth without breadth, securitization embodied the opposite. It proved that credit could scale to trillions, but the trust underpinning it was fragile, manufactured and costly.

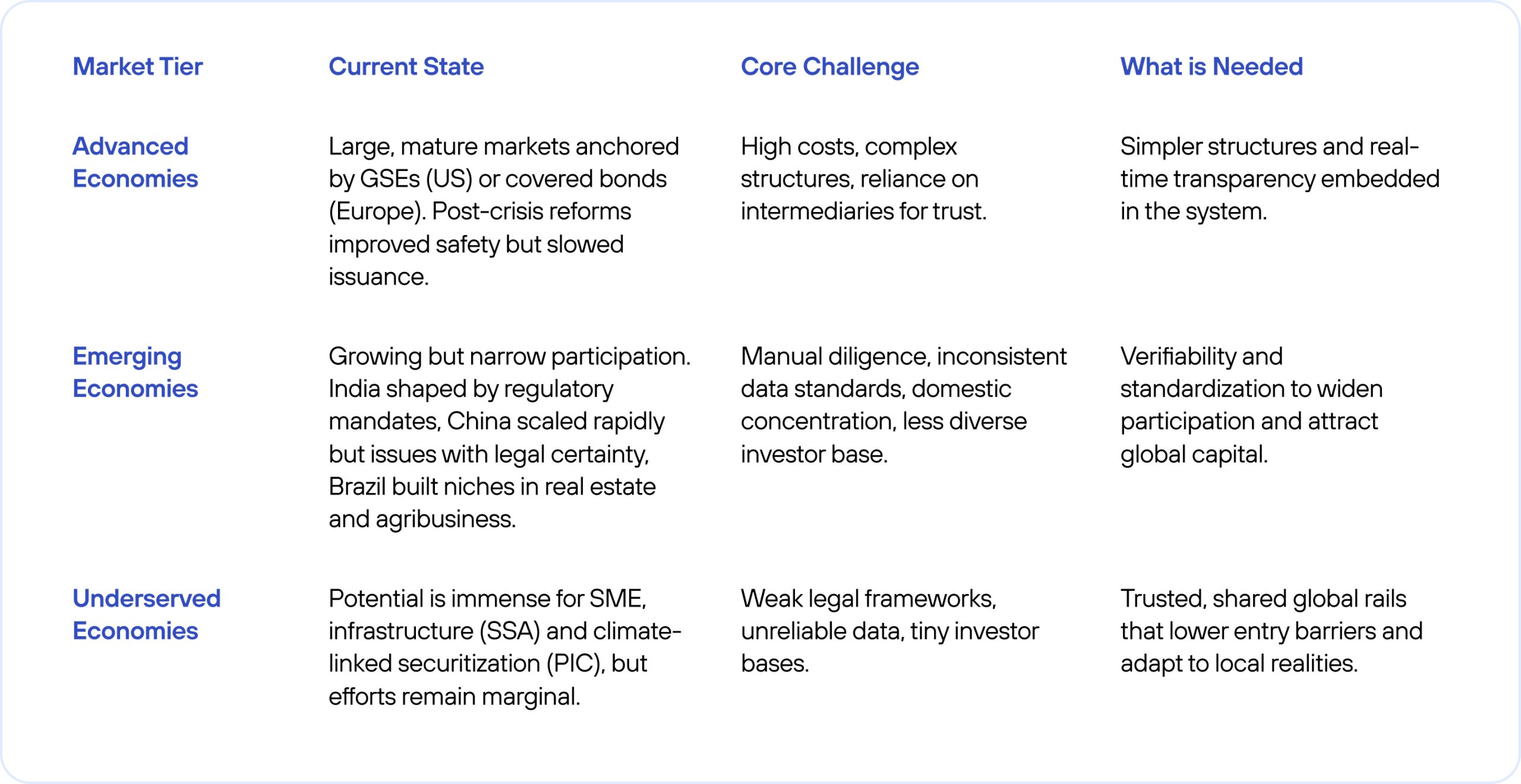

A Global Diagnosis of Securitization Today

The story of securitization is not uniform. Its trajectory looks at very different types of markets, yet the pattern is strikingly similar: scale is achieved in pockets, but trust and transparency remain elusive.

Across all three tiers, the story is different but the diagnosis is the same. Everywhere, the challenge is to embed verifiability and trust at the system level rather than rely on intermediaries or bilateral relationships to enable greater market participation.

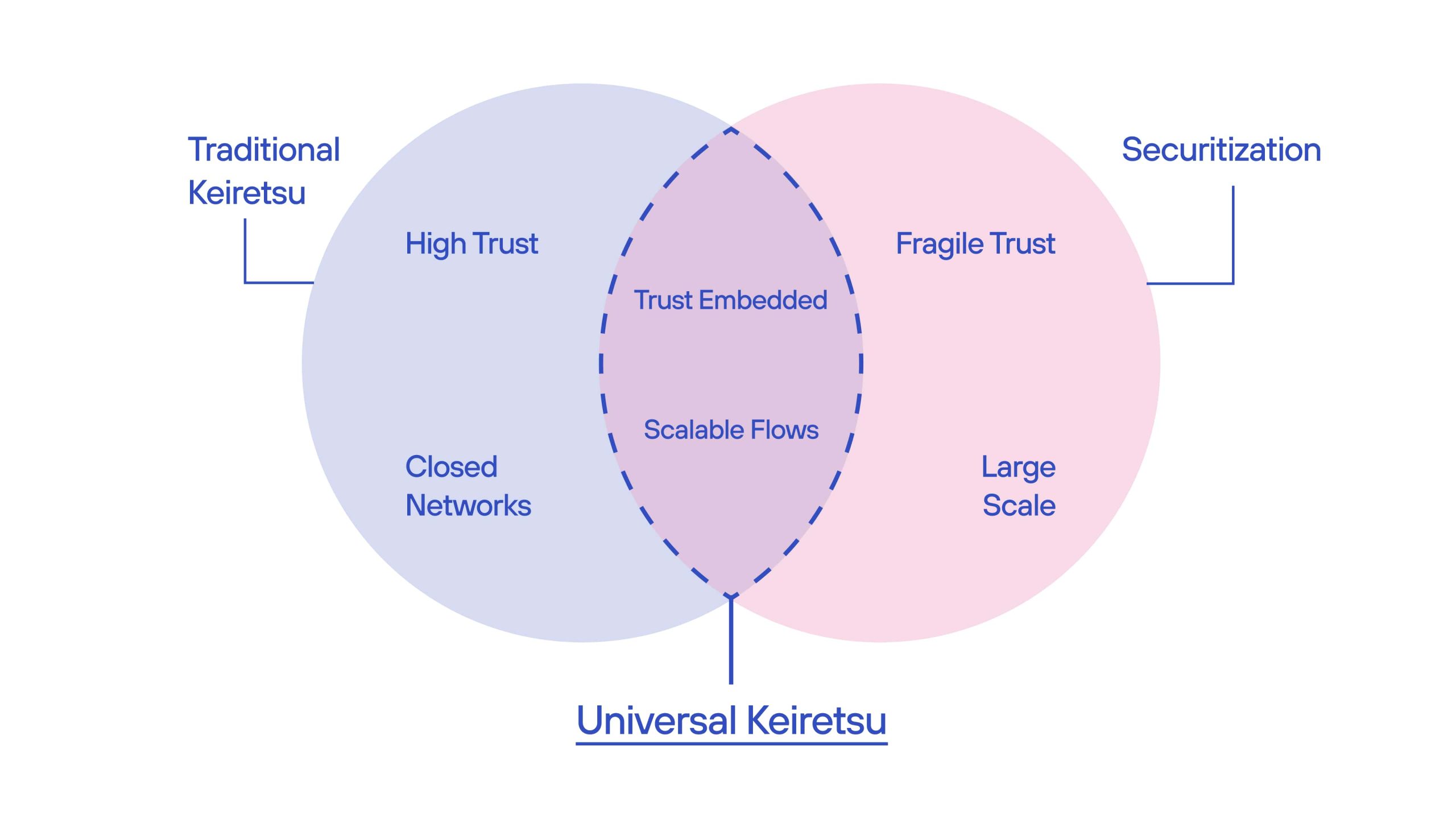

The Missing Middle: Toward a Universal Keiretsu

History has given us two powerful but incomplete models. Keiretsu showed how credit could be anchored in deep trust but confined to closed circles. Securitization showed how credit could scale across trillions but at the cost of fragile and manufactured trust.

The central question is whether scale and trust must always trade off. What if the two could reinforce one another?Today technology gives us the opportunity to combine the best of both. We can imagine a “Universal Keiretsu”, an interconnected network where credit can move with the openness and scale of global markets while carrying the embedded trust and shared knowledge that made older systems resilient. Unlike the closed networks of the past, this model would be built on digital rails designed to be transparent, verifiable and programmable from the start.

In such a system…

- Data is not hidden in silos but flows as shared truth visible to participants.

- Trust is structural, encoded in rules that govern risk-sharing and cash flow distribution.

- Participation broadens, with barriers of cost and diligence lowered so that new participants can join alongside large institutions.

This “Universal Keiretsu” is not a metaphor but an achievable architecture. This cannot be built on closed, proprietary rails. Digital platforms may streamline a single deal, yet fragmentation persists when every institution or jurisdiction runs on its own systems. What is needed is shared infrastructure, a common language for how data is verified, how rules are applied and how assets move. Just as the internet standardized information exchange, finance now requires open rails for the exchange of value.

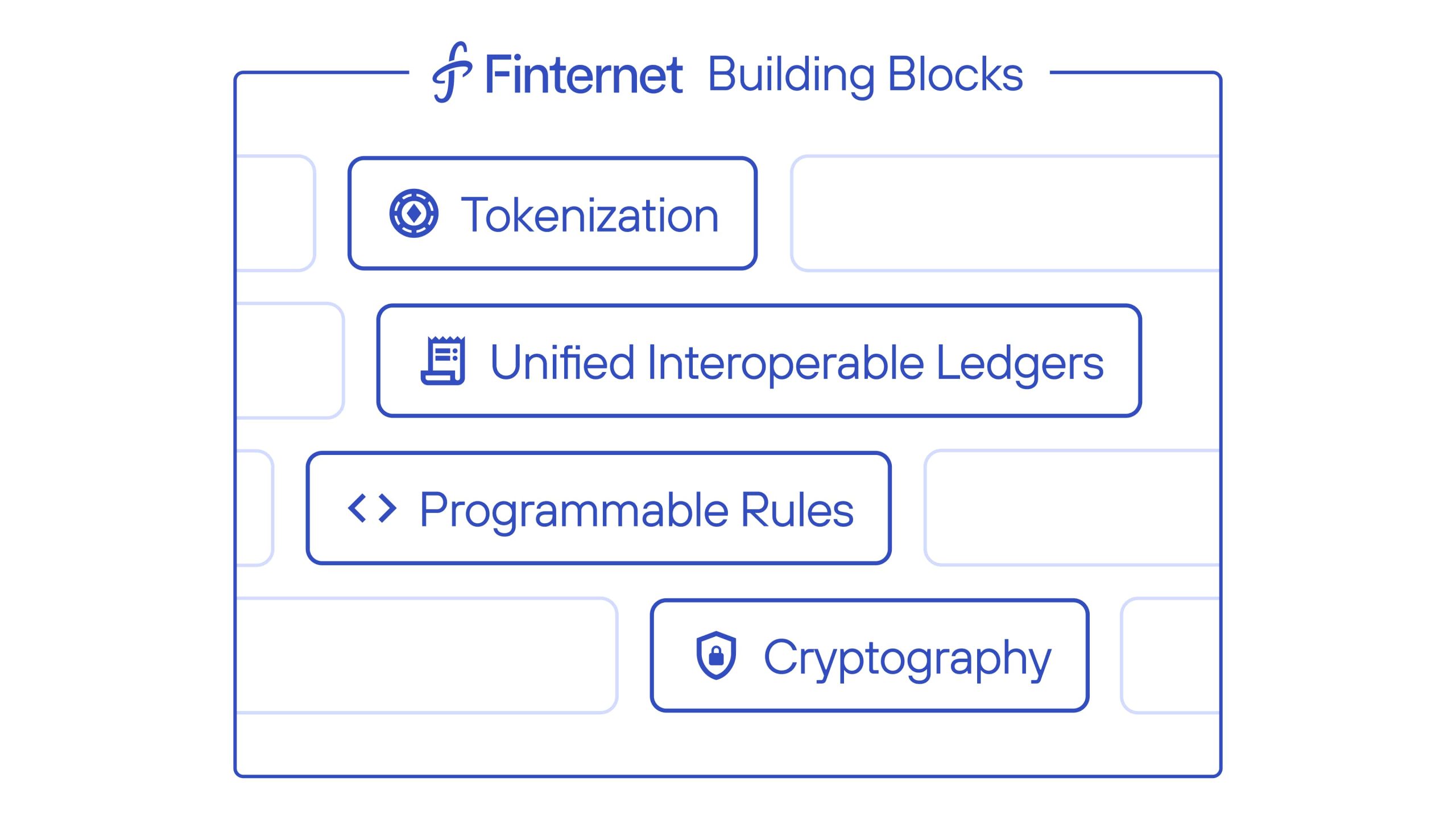

Building the Universal Keiretsu with the Finternet

The Finternet is one such foundation. It is designed around three principles: it is user-centric, placing individuals and institutions at the center of their financial lives; unified, connecting fragmented systems into a shared backbone; and universal, enabling participation across borders and asset classes.

Technically, this is made possible by four primitives:

In the original Keiretsu, a main bank anchored trust. In the imagination of the Finternet, the network itself becomes the anchor… an open, neutral backbone where trust is structural and capital can circulate with confidence across institutions, sectors and borders.

For securitization, the implications are immediate. Many of the pain points holding the market back map directly to what the Finternet’s architecture can resolve:

- Opacity → Shared Truth

Investors today depend on static PDFs, ratings and intermediaries for visibility. On the Finternet, loan-level data is recorded once, cryptographically signed and made available in real time to authorized parties. Claims turn into verifiable records. - Complexity and Cost → Programmable Compliance

Traditional securitization depends on layers of lawyers, trustees and intermediaries to enforce covenants and distribute cash flows. On the Finternet, compliance and reporting requirements can be expressed as code. Smart contracts execute them automatically, embedding trust into the system itself and lowering issuance costs. - Information Asymmetry → Broader Participation

Smaller originators and new investors are often locked out by high diligence costs and inconsistent data. Standardized, verifiable digital records lower entry barriers. Tokenized fractional securities let even modest investors participate, deepening the investor base and improving liquidity. - Jurisdictional Fragmentation → Interoperability

Every cross-border deal today requires bespoke contracts and duplicate due diligence. With modular legal and regulatory rules attached to the asset itself, pools can move across markets seamlessly, respecting local requirements while plugging into global capital. - Regulatory Blind Spots → Observability with Privacy

Supervisors currently see only delayed snapshots of systemic risk. The Finternet can enable regulators permissioned access to live pool health, preserving borrower privacy while strengthening oversight.

Together these shifts turn securitization from a mechanism often constrained by opacity, cost and fragmentation into one where scale and trust reinforce one another by design.

Conclusion

Securitization is a vast and diverse market, spanning asset classes, structures and regulatory models. What ties them together are the fundamentals: credit must be made verifiable, risks must be managed transparently, and flows of capital must be trusted across participants.

A modular Finternet architecture addresses these foundations, and once they are in place, the possibilities multiply. Entirely new classes of securitized products become viable. SME portfolios can be tokenized and offered to global impact investors with real-time monitoring. Governments in small economies can package climate-linked infrastructure receivables and place them confidently into international capital markets. Even familiar instruments like mortgage-backed securities can evolve into programmable, lower-cost structures that broaden investor participation.

At Finternet Labs, we are beginning to explore this frontier through structured pilots and collaborative cohorts. Each experiment is a step toward proving how shared rails can unlock both efficiency and trust. We invite lenders, investors, regulators and builders to join us to experiment, contribute and help build the future of finance.

This blog has been co-authored by Abhishek Rathi (abhishek.rathi@finternetlab.io), Sanmesh Kalyanpur (sanmesh.kalyanpur@finternetlab.io), Prasad Ajinkya and Vineet Nair (vineet.nair@finternetlab.io).

Editorial and writing support was provided by Vinith Kurian.